Pierre Charles Le Monnier on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pierre Charles Le Monnier (; 23 November 1715 – 3 April 1799) was a French

Pierre Charles Le Monnier (; 23 November 1715 – 3 April 1799) was a French

His persistent recommendation of

His persistent recommendation of

Lists of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

URL. Retrieved 19 February 2010. and was one of the 144 original members of the Institute. On 29 January 1745 he also became a member of the

Mitglieder der Vorgänger-Akademien

URL. Retrieved 19 February 2010. The crater Le Monnier on the

*''Histoire céleste'' (1741)

*''Théorie des comètes'' (1743, a translation, with additions of Halley's ''Synopsis'')

*''Institutions astronomiques'' (1746, an improved translation of

*''Histoire céleste'' (1741)

*''Théorie des comètes'' (1743, a translation, with additions of Halley's ''Synopsis'')

*''Institutions astronomiques'' (1746, an improved translation of

Pierre Charles Le Monnier (; 23 November 1715 – 3 April 1799) was a French

Pierre Charles Le Monnier (; 23 November 1715 – 3 April 1799) was a French astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, g ...

. His name is sometimes given as Lemonnier.

Biography

Le Monnier was born inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where his father Pierre

Pierre is a masculine given name. It is a French form of the name Peter. Pierre originally meant "rock" or "stone" in French (derived from the Greek word πέτρος (''petros'') meaning "stone, rock", via Latin "petra"). It is a translation ...

(1675–1757), also an astronomer, was professor of philosophy at the college d'Harcourt.

His first recorded astronomical observation was made before he was sixteen, and the presentation of an elaborate lunar map resulted in his admission to the French Academy of Sciences, on 21 April 1736, aged only 20. He was chosen in the same year to accompany Pierre Louis Maupertuis

Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (; ; 1698 – 27 July 1759) was a French mathematician, philosopher and man of letters. He became the Director of the Académie des Sciences, and the first President of the Prussian Academy of Science, at the ...

and Alexis Clairaut

Alexis Claude Clairaut (; 13 May 1713 – 17 May 1765) was a French mathematician, astronomer, and geophysicist. He was a prominent Newtonian whose work helped to establish the validity of the principles and results that Sir Isaac Newton had ou ...

on their geodetical expedition for measuring a meridian arc of approximately one degree

Degree may refer to:

As a unit of measurement

* Degree (angle), a unit of angle measurement

** Degree of geographical latitude

** Degree of geographical longitude

* Degree symbol (°), a notation used in science, engineering, and mathematics

...

's length to Torne Valley

The Torne, also known as the Tornio ( fi, Tornionjoki, sv, Torne älv, , se, Duortneseatnu, fit, Tornionväylä), is a river in northern Sweden and Finland. For approximately half of its length, it defines the border between these two countr ...

in Lapland. In 1738, shortly after his return, he explained, in a memoir read before the Academy, the advantages of John Flamsteed

John Flamsteed (19 August 1646 – 31 December 1719) was an English astronomer and the first Astronomer Royal. His main achievements were the preparation of a 3,000-star catalogue, ''Catalogus Britannicus'', and a star atlas called '' Atlas C ...

's mode of determining right ascension

Right ascension (abbreviated RA; symbol ) is the angular distance of a particular point measured eastward along the celestial equator from the Sun at the March equinox to the (hour circle of the) point in question above the earth.

When paired w ...

s.

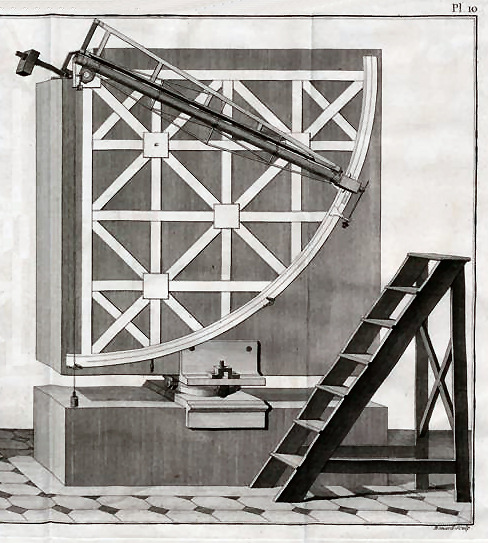

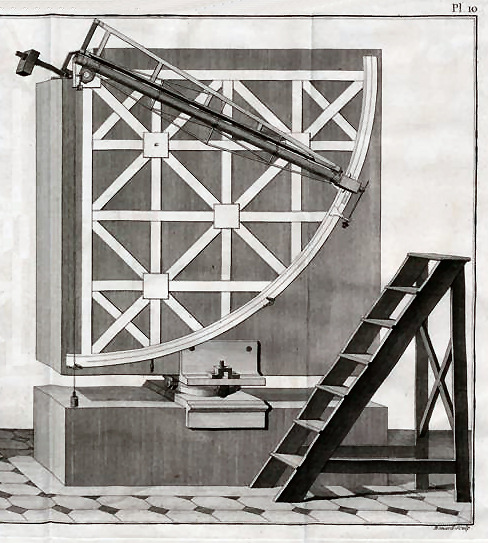

His persistent recommendation of

His persistent recommendation of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

methods and instruments contributed effectively to the reform of French practical astronomy, and constituted the most eminent of his services to science. He corresponded with James Bradley

James Bradley (1692–1762) was an English astronomer and priest who served as the third Astronomer Royal from 1742. He is best known for two fundamental discoveries in astronomy, the aberration of light (1725–1728), and the nutation of th ...

, was the first to represent the effects of nutation

Nutation () is a rocking, swaying, or nodding motion in the axis of rotation of a largely axially symmetric object, such as a gyroscope, planet, or bullet in flight, or as an intended behaviour of a mechanism. In an appropriate reference frame ...

in the solar tables, and introduced, in 1741, the use of the transit-instrument at the Paris Observatory. He visited England in 1748, and, in company with the Earl of Morton

The title Earl of Morton was created in the Peerage of Scotland in 1458 for James Douglas of Dalkeith. Along with it, the title Lord Aberdour was granted. This latter title is the courtesy title for the eldest son and heir to the Earl of Morto ...

and James Shore

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

the optician, continued his journey to Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, where he observed the annular eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six mon ...

of 25 July.

The liberality of King Louis XV of France

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

, in whose favour Le Monnier stood high, furnished him with the means of procuring the best instruments, many made in Britain. Amongst the fruits of his industry may be mentioned a laborious investigation of the disturbances of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

by Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

, the results of which were employed and confirmed by Euler in his prize essay of 1748; a series of lunar observations extending over fifty years; some interesting researches in terrestrial magnetism

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic fi ...

and atmospheric electricity

Atmospheric electricity is the study of electrical charges in the Earth's atmosphere (or that of another planet). The movement of charge between the Earth's surface, the atmosphere, and the ionosphere is known as the global atmospheric electr ...

, in the latter of which he detected a regular diurnal period; and the determination of the places of a great number of stars, including at least twelve separate observations of Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus ( Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars), grandfather of Zeus (Jupiter) and father of ...

, between 1750 and its discovery as a planet. In his lectures at the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris n ...

he first publicly expounded the analytical theory of gravitation

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stron ...

, and his timely patronage secured the services of J. J. Lalande for astronomy.

Le Monnier's temper and hasty speech resulted in many arguments and grudges. He fell out with Lalande "during an entire revolution of the moon's nodes". His career was ended by paralysis late in 1791, and a repetition of the stroke terminated his life. He died at Héril near Bayeux. By his marriage with Mademoiselle de Cussy he left three daughters, one of whom became the wife of J. L. Lagrange.

Le Monnier was admitted on 5 April 1739 to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

,The Royal SocietyLists of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

URL. Retrieved 19 February 2010. and was one of the 144 original members of the Institute. On 29 January 1745 he also became a member of the

Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

.Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der WissenschaftenMitglieder der Vorgänger-Akademien

URL. Retrieved 19 February 2010. The crater Le Monnier on the

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

is named after him.

Works

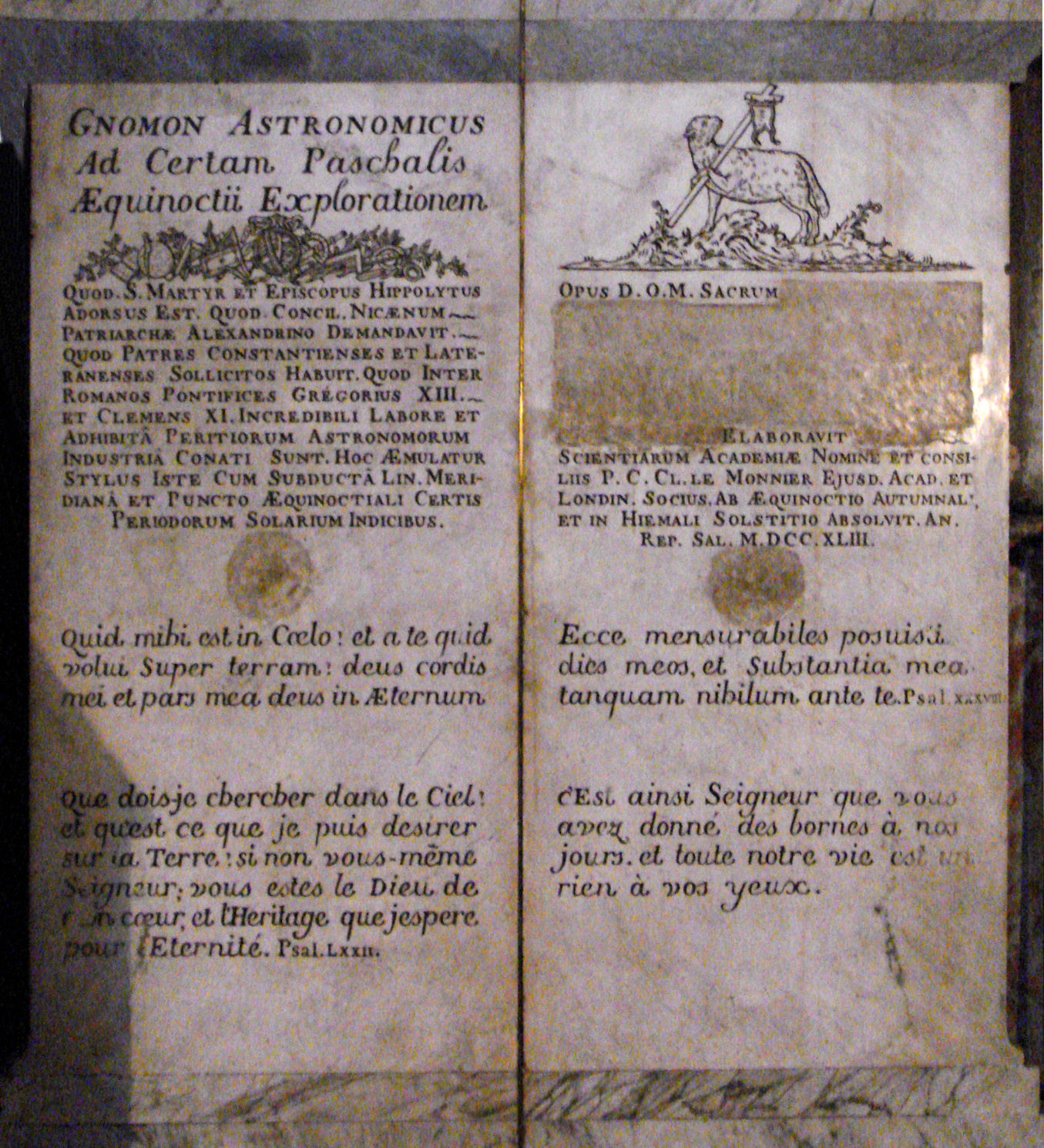

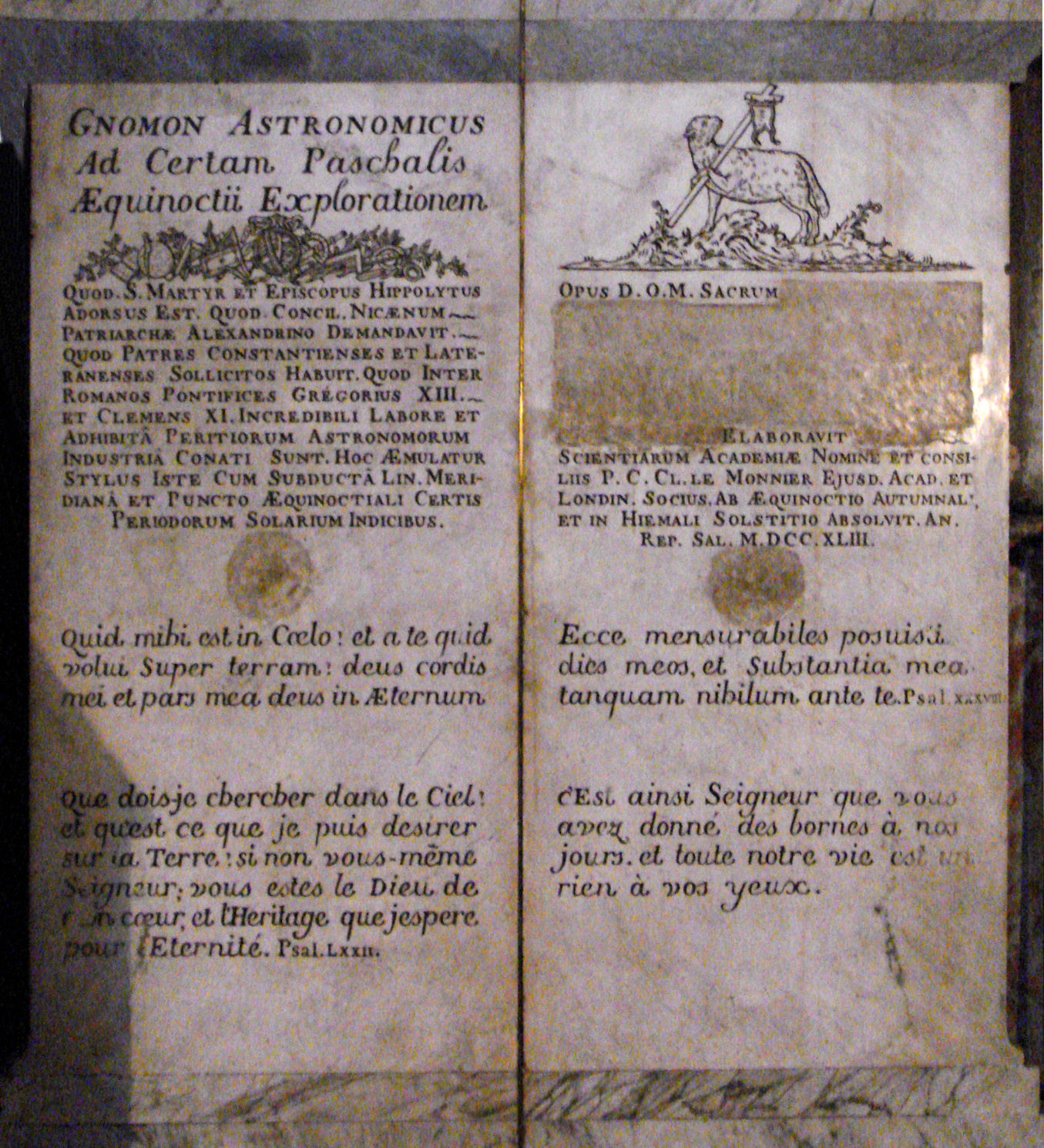

*''Histoire céleste'' (1741)

*''Théorie des comètes'' (1743, a translation, with additions of Halley's ''Synopsis'')

*''Institutions astronomiques'' (1746, an improved translation of

*''Histoire céleste'' (1741)

*''Théorie des comètes'' (1743, a translation, with additions of Halley's ''Synopsis'')

*''Institutions astronomiques'' (1746, an improved translation of John Keill

John Keill FRS (1 December 1671 – 31 August 1721) was a Scottish mathematician, natural philosopher, and cryptographer who was an important defender of Isaac Newton.

Biography

Keill was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on 1 December 1671. His f ...

's textbook)

*''Nouveau zodiaque'' (1755)

*''Observations de la lune, du soleil, et des étoiles fixes'' (1751–1775)

*''Lois du magnétisme'' (1776–1778)

References

;Attribution *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Le Monnier, Pierre 1715 births 1799 deaths Scientists from Paris 18th-century French astronomers Members of the French Academy of Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society mr:पियरे ले मॉनिये